We are where we are because of earlier actions and humans. History, and the people who shaped it, have immense value and we do well to remember them, the lessons learned and the world they helped to create - good or bad.

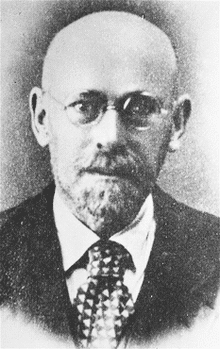

Janusz Korczak (1878 – 1942), doctor, early-years educator and writer, was born to a Jewish family in Poland - which at the time was a part of the Russian Empire. He attended a traditional school with quite rigid rules but due to the mental disability of his father, had to work and provide for the family from the age of 15-16. Despite this he was still able to graduate from Warsaw University (Medical Faculty) and to travel in Switzerland and Germany – all at his own expense – to further his knowledge in particular in childhood education.

image from Wikipedia

He always worked with young children, founding his own orphanage for Jewish children in 1911 and managing various similar institutions in Poland and, later, Ukraine. But, Janusz Korczak had his name forever written in history when in World War 2 when he refused to leave to safety, choosing instead to share the fate of the 200 Jewish children in his care. There is no shortage of heartbreaking material surrounding that bleak period, but here we focus on Korczak’s thoughts and ideas about early education. Approximately a contemporary of Maria Montessori, most of his principles sound familiar and sensible, almost obvious, now. But in those early days they were very advanced and are consequently really noteworthy.

Some of the quotes or examples below should be read with the understanding that this was a much different era to today. He had a remarkable mind, more so when placed in the context of his time.

"Children are not people of tomorrow; they are people today” - Korczak wrote in 1919 in his work ‘How to love a child’. “They have a right to be taken seriously, and to be treated with tenderness and respect. They should be allowed to grow into whoever they were meant to be” he said. “The ‘unknown person' inside of them is our hope for the future."

“What is it”, - asks the child pointing at the globe. “Is it a ball?”

“Yes.” – says the teacher.

“What kind of ball is it?”

“Well, it’s the Earth, not a ball. On it there are houses, horses, trees, your mommy.”

“My mommy?” – the child is visibly concerned and doesn’t proceed with questions.

Fundamentally, he believed that the key to being a good early childhood educator is to love children while for mothers (whose love goes without saying) the best understanding of parenting would come “from within” and not from books.

Korczak also underlined the idea that now is widely accepted but wasn’t that obvious in the beginning of 20th century: all children are different from each other. He said it’s no use to give a child a “perfect” example to follow. The key is observation and understanding of the child’s particular potential. This results also in Korczak’s principle of “Realistic Requirements”. For example, a child who easily becomes aggressive - according to Janusz Korczak - can’t just become calm and positive because we tell him so, but you can ask him to measure his anger and reduce it to, say, one time per day.

With rights, felt Korczak, children also needed to understand responsibilities. He underlined that instead of forgiving everything just because they are children, educators and parents should not forget about their own rights too, and should point out a problem to children (such as if they hit or mistreat or bite the parent or something similar). He was, however, absolutely against physical punishment, a method of control and punishment widely used in those days. As he writes in his book “Child’s right for Respect” of 1929:

"In what extraordinary circumstances would one dare to push, hit or tug an adult? And yet it is considered so routine and harmless to give a child a tap or stinging smack or to grab him by the arm. The feeling of powerlessness creates respect for power. Not only adults but anyone who is older and stronger can cruelly demonstrate their displeasure, back up their words with force, demand obedience and abuse the child without being punished. We set an example that fosters contempt for the weak. This is bad parenting and sets a bad precedent.”

His views sometimes were quite extreme and arguable – or maybe too thought provoking even for today, 100 years after his first big work was published. He believed that the goal of education was to prepare a child to live in a real world, not in a perfect world. In his words: “…It is often forgotten that we need to teach a child not only to appreciate the truth, but also to recognize the lie, not only to love but also to hate, not only to respect but also to despise, not only to agree but also to disagree, not only to obey but also to rebel…” Expressed in this way today, probably even then, this would be a difficult argument to sustain. But he exaggerates the point to promote enquiring minds and minds that also don’t automatically accept everything at face value. With even adults being captured left and right by scams these days who is to say he had not got it right – even if expressed in a different way.

Fortunately, many children today grow up surrounded by care and are well aware of their rights, so we can say the world has advanced in these past 100 years. However, is the present educational system, especially at later stages, often unable or unwilling to take into consideration children’s and teenagers differences, where some qualities and skills are clearly more rewarded than others? The world is changing rapidly and with it comes the continued need for thoughtful innovation and innovators in early childhood education to fit better with the needs of today’s and tomorrow’s world.